In the 19th century, the consumer revolution swept through cities and towns, from the homes of aristocrats to the middle class to the poor. Both men and women were involved in consumption, however, in different ways.

Books, fish, laces, dumplings, mirrors

In the early 1900s, the Jewish actor Alexander Granach, who was born in the village of Verbivtsi in the Ivano-Frankivsk region, neighboring Lviv’s region, visited Lviv and was impressed by the size and number of markets, entertainment, and other establishments. However, everything was similar to the situation in his hometown of Horodenka – except in scale.

«People were selling fruit on the sidewalks and street corners. Posters were hanging all around advertising various soaps, Kathrein’s malt coffee, restaurants and a circus with dancing horses, Polish opera, Ukrainian tricks, and Jewish singers from Brody. And so many markets! Especially one in front of the school, where people mixed and bought all sorts of things: books, fish, laces and dumplings, raw and cooked meat, butter, cheese, iron, mirrors, bread, dresses, kvass, suits, soups, chickens, cats, toys–all mixed up! Every day the same chaos, and despite the fact that everything did impress me, it still reminded me of Horodenka. On a different scale–ten times more, a hundred times more people, but no surprises, no miracles.»

(Alexander Granah «Here comes the man»)

The market in Lviv

Everything Alexander Granach observed was the part of the revolution that began in the late 18th century. People bought and consumed more, the comfort level and people’s needs rose simultaneously. Special items began to denote social status: gold watches, or elements of a wealthy interior. The middle class sought to acquire high status items to equate with the aristocracy. The shop inventories, which have been compiled together with wills, have allowed us to learn that the number of personal belongings increased.

Eventually, the industrial revolution accelerated consumption, which became part of urban life: people began to celebrate birthdays, Christmas, and other holidays with gifts or new toys for children that appeared to meet the new needs and capabilities of society.

The consumer urban space expanded and changed: small shops, cafes, confectioneries appeared, markets were being upgraded and rebuilt, shopping arcades were being arranged, followed by the final product of the consumer revolution: department stores.

Does the consumption have gender?

The consumer revolution changed cities, and at the same time, relations in society, particularly gender roles. Paradoxically, in the 18th century women were more involved in the social life and economic activities of their households, but the 19th century defined a new domesticity: Middle-class women of this era were responsible for the home, providing a certain level of comfort and raising children. Men were responsible for the so-called luxury consumption: the purchase of high status expensive watches, horses, while spending time in serious institutions in company with other men.

At the same time, women became both subjects and objects of consumption. On the one hand, they were responsible for buying things for the household and food products, and on the other, images of women, including all sorts of mannequins, were used to sell various goods. In general, the symbol of femininity prevailed in consumption. This is also connected, says Vladyslava Moskalets, with the first critique of consumption:

«The first critique was that consumption exploited weaknesses. Since the symbol of weakness at this time was a woman, she was accused of being susceptible to consumption. And they blamed, of course, this new commercial culture which used beautiful shop windows, advertisements, fashion magazines to seduce a woman and extort money from her.»

Both women and men were involved in the process of consumption; however, in different ways and with clearly defined «spheres of influence.» Public spaces were also implicitly divided by gender and trade (profession).

Markets: space for wives and maids

At the beginning of the 20th century, Lviv had many, mostly pop-up, markets. The city tried to organize and regulate them following the trends of Western Europe. The new markets were arranged with roofs or shelters, offering the opportunity to hide from bad weather. Then there was the idea that the market could not be a place where you could be fooled, so there were often scales on the shelves so that people could weigh the purchased goods.

The photos show that most market visitors were women: wives, or maids in special dresses. The markets became a place where class differences were both manifested and blurred. Here, no one could fault the women for leaving home without an escort. It was the place of their responsibility and a moment when they could take care of the home. Women who came from the villages with their goods were also behind the counters. Therefore, we could say that the market was a women’s space on both sides.

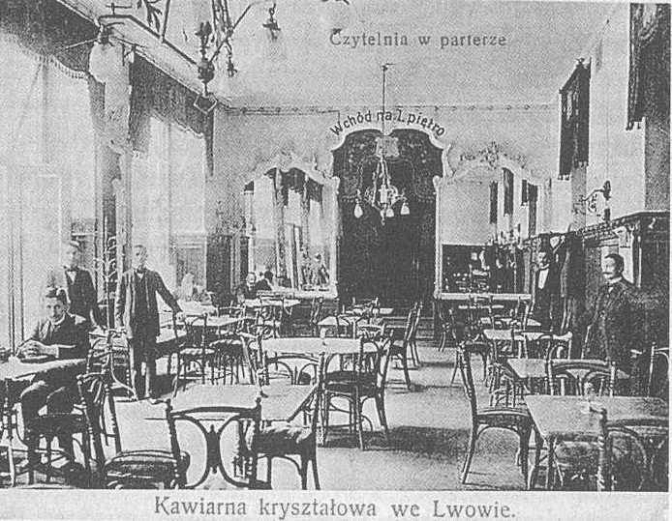

Cafe: the only woman here is … the owner

When women arranged the house and took care of the kitchen, the men spent time talking in cafes which were then considered a men’s space: Men prevailed here both among the staff and among the visitors. In general, cafes were called the «third space»: not entirely public and not entirely private. Here you could have a personal conversation or move the tables together to attract more conversants. There were many cafes in Lviv; because of this we have a traditional perception of Lviv as a city of coffee. However, cafes of that time were criticized for provincialism amid their attempts to imitate Paris and Western Europe. For instance, Lviv had a «Wiener Kaffeehaus» and a «Central cafe,» copying Vienna and Paris, respectively

«As someone rightly said, there can easily be a Paris cafe in Paris, but there will never be a Lviv cafe in Lviv», Vladyslava Moskalets adds.

All establishments tried to demonstrate their belonging to the Western world. Each cafe had its own specialization or target audience, which was even indicated in the guides: for artists, for oil entrepreneurs, etc., so that the traveler would not accidentally go to a cafe with the wrong audience.

In such a strictly regulated world, it was difficult for women to fit into public life. The Wiener Kafeehaus, for example, was proud of the fact that they had never had women even at the buffet; the only woman was the owner. The practice of running such businesses by women was acceptable, but they did not appear at the tables.

Thanks to emancipated women who challenged such social norms, the situation changed. Even before the interwar period, cafes became a completely normative space for women.

Another place that was completely feminine: confectioneries.

«Confectioneries were less serious places than cafes. An institution where there were no newspapers, but plenty of cakes instead, was considered quite legitimately female,» Moskalets says.

Passages: being a woman is too noticeable

The idea of shopping arcades or passages appeared in France in the early 19th century, and by the middle of the 20th they had become popular. An ordinary street with houses was covered with metal arches and a glass roof, turned into a sheltered place housing hairdressers, cinemas, shops, cafes, and many other establishments.

The passages embodied the idea of modernity: open and sheltered spaces at the same time that let in different people and allowed the classes to mix. They were associated with the figure of a flâneur, French for loungers or stroller, an outside observer who enjoys a walk through the passage and might not even go to any of the stores. The construction of passages stopped at the beginning of the 20th century, and they were replaced by department stores, which were more convenient in terms of fire safety.

There were many passages in Lviv: between Kopernyka and Kruta (Voronoho) streets there was Mikolasch Passage, 120 meters long and 18 meters wide. The Opera Passage on Svobody Boulevard has survived to this day. The 19th-century passage was a perfectly acceptable place for women to walk. However, a woman’s inclusion in this public space inevitably raised another question: How safe did she feel there? The woman was by definition conspicuous, so the opportunity to blend in with the crowd and observe city life was lost to her. However, there were also ladies who disguised themselves: They wore men’s clothes so as not to draw too much attention.

A glaring Case in the Passage

1911, end of March. An unprecedented thing happened in Mikolasch Passage as recounted in the Kuryer Lwowski newspaper: A woman went for a walk in trousers and she did not even disguise herself as a man. Woman in pants! Unwritten social rules were violated. A large crowd gathered around her, whistling and shouting. The woman had to flee to the Grand Hotel, and the police had to intervene to stop the crowd.

Unwritten social rules for women strongly determined their presence in urban spaces: when, with whom and how to appear, as well as how not to go out, because the poor woman could be punished for the simple pants.

The passages were open all the time. During the day, they were quite respectable places for the middle class, and in the evening illegal money changers, profiteers, and prostitutes gathered there. This was one of the things that were also fascinating in the passages: Their fluidity and variability within just one day.

The boundaries between public and private spaces in Lviv were quite fluid, and women could appear in the urban spaces and not just be imprisoned at home, but it certainly depended on their social and marital status. Lviv developed rapidly during the consumer revolution, offering new and different ways of coexistence and entertainment, as well as new forms of functioning for women, along with the dangers.

by Kateryna Bortnyak based on a lecture by Vladyslava Moskalets

translated to English by Dmytro Borysov

(The lecture was part of the Women’s Dimensions of the Past lecture series, organized in cooperation with the Center for Urban History and the Ukrainian Association of Women’s History Researchers with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Kyiv-Ukraine Office).

Photos provided by Vladyslava Moskalets